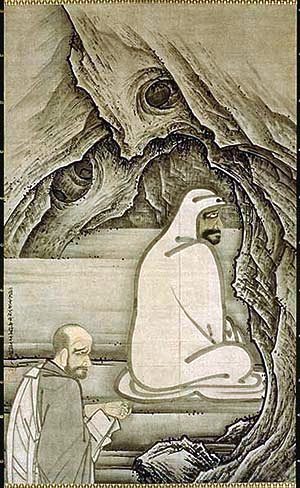

This man was a young man named Eka, who had traveled across the high mountains of eastern China in the cold of December. Eka was standing in waist deep snow outside of Bodhidharma's cave, cold tears freezing as they were running down his face. Inside the cave, Bodhidharma was in deep meditation.

As he waited outside, despite the hardship, despite the suffering, Eka began looking within himself and began to let go off all aspirations and attachments. He simply waited outside for Bodhidharma to recognize him, not for his own sake or for any gain, but because he knew it was right somehow. But Bodhidharma ignored Eka, and stayed inside. Eka strengthened his resolve; he let go of all ambitions and all his ego attachments.

Finally, at dawn, when the long cold night finally ended, the teacher emerged from the cave, seeing that his new student had indeed progressed quite nicely. Bodhidharma took pity on Eka and asked,“What are you after, standing there in the snow for such a long time?” Eka's tears of sorrow were falling even more profusely as he answered, “I simply ask that you have compassion on me and open the gate to what I long to learn.”

Bodhidharma said, “That gate can only be opened for those who ceaselessly practice what is hard to practice and who ceaselessly endure what seems beyond endurance. But be warned, if you still rely upon a frivolous heart or on a prideful and conceited mind, you will toil in vain.”

Eka was encouraged by Bodhidharma's words, but he knew he had to make one more demonstration to prove his worthiness to the Master. So Eka secretly took out a very sharp sword and with one quick stroke, cut off his left forearm. He took his left arm and threw it before Bodhidharma and said, ”If you don’t turn immediately towards me, I am going to cut off my head too.”

Bodhidharma quickly turned, and said, ”So you have come! I have been waiting for nine years.” Bodhidharma added, "In their seeking the Way, all the masters, from the first, have laid down their own bodies for the sake of the Way. Now you have cut yourself free right before me, which is proof that there is good in what you are seeking.”

For the next eight years, Eka served as attendant to the Master in all his endeavors. He was a great, reliable spiritual friend for both ordinary people as well as for those in loftier positions, and he was a great teacher of the Way. And when the time came, Bodhidharma chose him as his successor.

Eka was inspired by Bodhidharma's words to arouse wisdom and finally cut himself free from any last vestiges of clinging and grasping, represented by his left forearm, and he then presented himself and his understanding to Bodhidharma for approval. The ancient masters maintain that when Eka cut off his arm, there was no effort involved; he was so relaxed, so trustful. He was relaxed and trusting because he had learned to let go. His ego was firmly in check.

The story of Bodhidharma and Eka is about letting go – and so is Jesus' First Beatitude (in today's Gospel text from Matthew 5):

Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. (Matthew 5:3)

When Johannes Jessen translated that sentence into the Lower German dialect of my home in Northern Germany, he rendered it this way:

Selig sünd de Minschen, de as beddelarme Lüd vör Godd sin Dör kamt un weet, dat se vör em niks uptowiesen hebbt -- ehr hört dat Himmelriek to! (In plain English: Blessed are those who come to God's door as people who are dirt poor and know they have nothing to show for themselves -- the Kingdom of Heaven is theirs.)

German mystic Meister Eckhart offers this interpretation: “A poor man is one who wants nothing, knows nothing and has nothing.”

- Eckhart says we need to be “poor of will”, by wanting just as little now as when we were too small and immature to have our current desires.

- Eckhart says we need to be “poor of knowledge”, by freeing ourselves from all the knowledge that has been stuffed into us, and by realizing that such knowledge only ties us to this street theater called "the world".

- Eckhart says we need to be “poor of having”, by freeing ourselves of all desire to control things with the things we own or cling to. He traces this thought even into our image of God, saying, “I pray to God to make me free of my ideas of God.” If we have ideas of God, we still retain control, and as truly detached believers we must surrender all control.

How can we achieve such freedom? Echoing the warning Bodhidharma had for his young student ("If you rely upon a frivolous heart or on a prideful and conceited mind, you will toil in vain"), Eckhart tells us to start the process of putting our ego in check in a very simple manner: “Take a look at yourself, and wherever you find yourself, deny yourself. That is best of all.”

Martin Luther, a theological giant of great fame and vast influence, said these words on his death bed: “We are beggars – this is true.” That's being “poor in the spirit” -- knowing that we come to God as people who have nothing to show for ourselves. And there's nothing wrong with that -- in fact, it's the only way to be right, for "without poverty of spirit, there can be no abundance of God" (Oscar Romero, martyred Archbishop of El Salvador).

What is the result of such freedom? In embodying "a true spirit of poverty which makes the rich feel that they are closer brothers and sisters of the poor, and makes the poor feel that they are equal givers and not inferior" (Oscar Romero), the People of God find themselves in an acute clash with the values of the world, exposing themselves as foolish misfits and outcasts, as "God's fools". Paul is very sober and clear-eyed when he says:

For the message about the cross is foolishness to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God. For it is written, "I will destroy the wisdom of the wise, and the discernment of the discerning I will thwart." Where is the one who is wise? Where is the scribe? Where is the debater of this age? Has not God made foolish the wisdom of the world? For since, in the wisdom of God, the world did not know God through wisdom, God decided, through the foolishness of our proclamation, to save those who believe.

As people who live by the Wisdom of God rather than under the Wisdom of the World, we know that our values do not conform to those of competition and domination that are propagated by the world around us. As the People of God we are truly "countercultural". Our culture teaches us to be selfish, but the cross beckons us to have compassion. Our culture condemns the poor and homeless and blames them for their misfortune, but the cross beckons us to embrace them as sisters and brothers. Our culture teaches us to look down on those who have less, but the cross beckons us to feed them.

Being countercultural carries the very real risk of suffering and the cross, but the rewards are manifold, and far from just otherworldly: as the People of God we can tap into what Rabbi Michael Lerner calls the "irrepressible elements of human nature" shared by all humanity; in his recent article on the "State of the Spirit", Lerner says:

Human beings share a deep yearning to live in communities that provide a sense of purpose to their lives. Yearning to transcend the narrow visions of material self-interest, we long to connect to something of abiding value. We share a hard-wired empathy and love for others, as well as a deep need to be recognized, understood and loved not for what we can do or deliver for others, but for our own intrinsic worth (what the Torah calls being created in the image of God). And we have an irrepressible instinct to seek freedom; creativity; artistic expression; higher and higher levels of understanding and consciousness; love and caring for others; the creation and enjoyment of beauty and pleasure; and both joyous celebration of and awe-filled responses to all the wonders of life in this universe.

Matthew 5:3; 1 Corinthians 1:18-31

No comments:

Post a Comment